Chief Shingwaukonse was a key leader who role asserts the Anishinabeg’s contributions, understandings and hopes in the War of 1812.

By virtue of being placed upon Turtle Island by the creator, the Anishinaabeg have always had to stand up for themselves and protect what was entrusted to them. This past winter saw a movement called Idle No More sweep the country. Many communities, universities, organizations, and allies hosted teach-ins and many people tweeted messages of solidarity. Posters were also made of famous chiefs who had made a stand in the past, such as Chief Sitting Bull and Chief Quanah Parker. The images were mostly of chiefs from the Plains nations, not Anishinaabe chiefs, which perhaps can be explained by the fact that Idle No More started in the Great Plains. There is nothing wrong with adopting those chiefs because of their principles but I think there is one chief who has been overlooked. This chief took a stand at a critical time in our history, a time when the colonial authorities were allowing mining prospectors and companies to take over our lands without having a treaty in place, and worse, without compensating the true owners of the land. If this Ojibwe Chief Shingwaukonse ‘Little Pine,’ had not taken a stand, I believe there may have been no treaties west and north of Parry Sound after 1840.

There is ample information about Shingwaukonse. In fact, a book has been written about him and his influence called The Legacy of Shingwaukonse by Janet Chute. Shingwaukonse was from Baawting (Sault Ste Marie) area, and his mother was of the crane clan. His father was reportedly a Zhaaganaash (Englishman). Although biologically a mixed blood, he was raised as an Anishinaabe and identified as Ojibwe: he would later advocate on behalf of the Métis living at the Sault and attempted to have all of them enrolled in his band, an effort that was partially successful.

Shingwaukonse was a noted member of the Midewiwin (a medicine society) who had attained great spiritual power through repeated fasts. Shingwaukonse recalled, “When I was young I did not conduct myself as many of the young men do now – No – and I had good reason. I had a good mother who gave me a coal to black my face and then I was obliged to fast. When I became a man I ceased to fast.”[1]

German travel writer, Johann Georg Kohl met Shingwaukonse and obtained a good deal of information about Anishinaabe customs, specifically the use of pictography on birch bark scrolls. Likewise, Indian Agent and ethnologist Henry R. Schoolcraft, also interviewed Shingwaukonse numerous times to find out more about certain rock painting sites as well as the meaning of the symbols used in the Ojibwe pictographic writing system. Chief Shingwaukonse was a learned man and he stated numerous times in council that he listened to his Elders. “I remember seeing and hearing three of my ancestors and they were very old men and I remember these old men used to say to me when I was very young, ‘Grandchild you will see two nations of white men come to these lands who will act very differently to you, one from the other nation will do you much injury, the other will always be kind to you, mind what I say,’ said the old man, ‘my grandchild and give yourself to the latter.’ I never forget this but ever think in my heart of my grandfathers words.”[2]

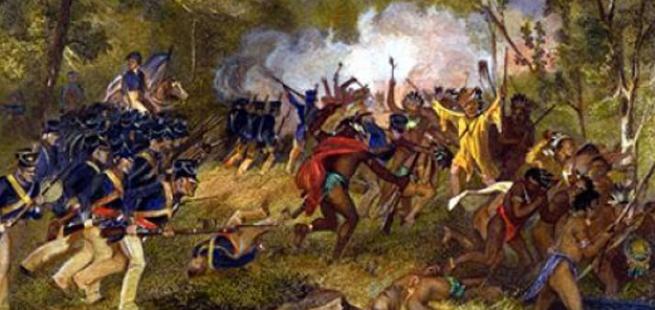

Bearing these memories in his mind and heart, Shingwaukonse weighed his options and decided to fight alongside the British during the War of 1812. He wrote of his service:

[T]he war commenced. I Chingwaokouse [Shingwaukonse] headed a party of 700 Indians and was at the taking of Mackinah we were successful and took the fort. In the summer I was on my lands in the centre of Lake Superior now the Long Knives’ land whence I was called to the Great Falls with my men…Three different days I led the attack on the Long Knives and much Long Knives’ blood was shed on those occasions for I conquered on the two first occasions and on the third was not [worsted] by the Nahtahwas who were opposed to us tho [sic] I suffered much and was myself wounded yet I beat them back we rushed too far in pursuit and many perished only two of us returned alive.[3]

For his services during the war, Shingwaukonse stated that he was made a chief. He was awarded a chief’s medal as well as the General Military Service medal for serving at the Battle of Detroit. He would later receive another medal from Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colbourne. Although Shingwaukonse was decorated for his service and designated as a ‘deserving chief,’ he lost some of his territory after the war. He wrote, “When the war was over the Chief spoke to me through my friend the late Mr. Askin and said, thank you Chingwaukouse [Shingwaukonse] many thanks to you. You shall never be badly off even your children will be looked after by the English, you have lost your land in the bargain made between us and the whites. Chose [sic] for yourself land in the neighbourhood of the Saut on the British side, have nothing to do with the Long Knives, you will soon find that you will be visited by good days which will not end as long as the world exists.”[4]

After the war, Chief Shingwaukonse enjoyed the benefits of his status as a “deserving chief”. This designation meant that one had distinguished themselves during the war or had been wounded during the war, and as such they were entitled to better quality of presents, such as three point blankets instead of two point, a rifle instead of a musket, as well as other items. These were called the “Indian Presents” and were the fulfilment of a treaty between 24 Nations and the British, called the Covenant Chain. This treaty was agreed to in 1764 and was the result of the great Odawa Chief Pontiac’s timely intercession. These presents were delivered annually at posts such as Michilimackinac, Malden, York, St. Joseph’s Island, and Manitowaning. The gathering for presents was a time to affirm the tenets of the Covenant but it was also a time to council with the British and air grievances. It was during these councils that Shingwaukonse demonstrated his abilities as an orator, a prized quality among the Anishinaabeg. At St. Joseph’s Island in July 1829, he stood up in council, holding a few strings of wampum in his hand and said, in reference to the Covenant Chain:

Father – The Great Master of Life gave us pipes and Wampum for the purpose of conveying our ideas from man to man. I return thanks to the Great Spirit that made me, and to my Great Father, the King, who supports me; what he promised to our forefathers, he continues to perform. He is charitable to the red skins.

Father – Two of my young men want bows [guns], and another wants a kettle; I have now finished speaking, my throat is quite parched with thirst, do give me a drop of your milk [rum] to wet it; this Wampum reaches to Penetanguishene, I will go there in future with my women and children, in hopes that my life may be prolonged.[5]

Shingwaukonse understood the principles of the Covenant Chain, he knew that the wampum belts represented a treaty in which the British had recognized the Anishinaabeg as allies, not as subjects, acknowledged that the Anishinaabeg owned the land (now called Aboriginal title), and that the British would adopt the Anishinaabeg and act as their father by offering them protection against unscrupulous traders and businessmen. Chief Shingwaukonse saw the great wampum belts, heard the speeches recited, committed them to memory, and knew the channels that he was to follow if he had a grievance. So, in 1837 at Manitowaning, at the newly lit council fire of the British and the Anishinaabeg, Shingwaukonse rose and addressed all assembled,

Father – The white people are in the habit of cutting timber on my lands and taking it to the American side of the river and, there, selling it for their own advantage.

Father – I cannot prevent them and I wish the laws of the white men may be put in force against them for they are doing me great injury.

Father – I wish to have means placed at my disposal in order that I may pay persons to protect my land.[6]

An increased number of immigrants arrived in Shingwaukonse’s territory and started to help themselves without asking. Shingwaukonse tried in vain to stop them and so took the next step which was to inform the Superintendent of Indian Affairs. This did not result in a resolution and the following year, again in council stated:

My Father – You wish to know my thoughts and they are these; those houses you see along the beach and the dwellers therein were never allowed by me or by my fathers, to have built or to clear the little land they have. [..]

My Father – Our place is becoming like a meadow for they have destroyed all the good timber about the place. I held a Council with them last fall, telling them, that they must pay attention to what I say, but they do not, they will not pay attention.[7]

Here the chief, no longer war chief but a convert to Protestantism, demonstrated his patience but also his knowledge of the foundational treaty between the Anishinaabeg and the British, the Covenant Chain. He knew that there had been no other treaty between his forefathers and these new settlers for his territory. He knew that they were squatting on his land and that an agreement needed to be in place. But being a peaceful man, he did not resort to force. The following year, again, he reported that the timber that had been cut resulted in a ‘meadow’ and that during his absence, the non-Native people had cut more timber but also started removing the grass from the meadows.

Father – I now wish to speak of the place where we now are and of the Country about us which belonged to my forefathers and first of myself. Last winter I went above the rapids to look for fish, for the support of my family. I discovered a large quantity of timber, cut into lengths hewed, and prepared to be transported to some place. All this was done without my permission, although I have again and again remonstrated on the subject to the government of our Great Mother […]

Father – When I returned last year from receiving my presents at Manitowaning, I found people from the territory of the Long Knives had come over and cut down a large quantity of grass growing on the meadows that have always supplied me with hay for my winter consumption. I sent a party of persons to arrest these persons, and bring away the boats which were loaded with hay from my meadows. The boats were brought away and moved near our village. In the night, a party of the Long Knives crossed the river and carried away the boats, and the hay with which they even loaded.

Father – The following day, my young men armed themselves and went to bring away the hay which was still left on the ground when it was cut. The Long Knives also armed themselves. When I discovered this I ordered my young men to return home, fearing the consequences of bloodshed, but feeling confident that our Great Mother would not permit her red children to be oppressed whilst living under her protection.

Father – I have been accused of cowardice, but I replied I was not a coward but wise!

Father – I now tell you plainly that it is useless for me to attempt to govern this place without your assistance.

Father – The Long Knives and many of your own white people have taken, and still continue to take from my land, great quantities of timber. I wish you to check these depredations.[8]

Although the Crown had promised to protect the Anishinaabeg from non-Native settlers, the superintendent stalled again and stated that he did not have the authority to answer but would check with his superiors. The superintendent did, however, take the time to state that “the trespasses on your property by American Citizens, you should not permit and were I [circumstanced] as you are, I would use force to prevent them. In the instance of the hay, you acted prudently but not wisely when you left the boat unprotected.” Here the superintendent blames the victim of the crime. Imagine if Shingwaukonse had forcibly taken back his property and allowed his armed young men to fight the Americans.

Shingwaukonse and his band maintained their livelihood while adjusting to the introduced religion they had adopted. Meanwhile, every year starting in 1836, the nations gathered at Manitowaning to re-affirm the Covenant Chain treaty and to receive their presents. The annual delivery of presents was a forum for the Crown to announce its policies. It was at Manitowaning on Manitoulin Island that the Crown tried to establish another model community where Anishinaabeg would be taught trades, how to read and write, and would receive religious instruction. The Crown representatives tried desperately to court Shingwaukonse to move to the island but he resisted all offers because he saw what was happening in his territory and the potential of being ripped off. In 1846 he changed strategy and instead of expressing his concerns in council, he instead wrote a petition to the Lieutenant Governor, stating one of the reasons he would not move to Manitoulin:

Great Father […] for some years great things have been found in their plans. I see men with large hammer coming to break open my treasury to make themselves rich & I want to stay and watch them and get my share.

Great Father – The Indians [incentive] get annuity for lands sold if ours are [not] fit in most places for cultivation they contain what is perhaps more valuable & I should desire for the sake of my people to derive benefit from them.

Great Father – My territory extends to [Michissiwton] there already have they found my rich things, but I know nothing of what is going on; I see the people pass and I hear what is said but I have no certain knowledge. I want always to live and plant at Garden River, and as my people are poor, to derive a share of what is found on my lands […] Already has the white man licked clean up from our lands the whole means of our subsistence, and now they commence to make us worse off, they take every thing away from us father […] Now my father, I called God to witness in the beginning and do so now again and say that it is false that the land is not ours, it is ours.[9]

Here, once again Shingwaukonse shows that he is shrewd but also knowledgeable. He knows that there are treaties elsewhere, he knows that other bands receive annuities for land sold, and he knows that there is a benefit to be had for his people if the principles of the foundational covenant are upheld. However, the government of that day had issues of patronage and conflict of interest; for example, many of those working in government were also shareholders in mining companies. The government dragged its feet and ignored Shingwaukonse’s appeals for justice.

Instead of stemming the tide of immigrants and prospectors, Father Menet, a Jesuit, noted in 1847 that “[F]or the last few years, the Sault has been visited by many people on their way up to the lake and in returning throughout the warm season. Boats, schooners and steamboats bring them to us by the hundreds. They look upon this country as an Eldorado… the main factor that increases the floating population of the Sault is mining.”[10] In 1848 he went to Bruce Mines, east of Sault, and noted that there were 25 houses there with more being built, but also stated that “you would think that you were in a fortress defending itself against incessant attacks from their enemies. Explosions could be heard at every moment that resembled volleys of heavy artillery. But in this case war was being made only against rocks.”[11]

Against this backdrop of industrial growth, Shingwaukonse and his son-in-law Chief Nabanegojing (Sayers) exhausted various diplomatic means such as written petitions and verbal complaints in council. Then, in 1848, they proceeded to Montreal to again meet once more with the Lieutenant Governor. Their appearance caused a ‘media’ frenzy, their picture was taken and their portraits painted by Cornelius Krieghoff. On top of that, the Montreal Gazette published a speech of the delegation along with the Lieutenant Governor’s response:

Father- Three years have passed since your white children, the miners, first came among us, and occupied our lands; they told us that we should be paid for them, but they wished to find their value. With this reply, at the time we were satisfied; but our lands being still occupied and claimed by them we became uneasy, and sent some of our Chiefs to see you in Montreal. You promised that justice should be done us, a year passed, and there is no appearance of a treaty; again we sent, again the same reply, and again last Autumn we sent and still there is no appearance of a treaty.

Father- We begin to fear that those sweet words had not their birth in the heart, but that they lived only upon the tongue; they are like those beautiful trees under whose shadow it is pleasant for a time to repose and hope, but we cannot for ever indulge in their grateful shades – they produce no fruit.

Father- We are men like you, we have the limbs of men, we have the hearts of men, and we feel and know that all this country is ours; even the weakest and most cowardly animals of the forest, when hunted to extremity, though they feel destruction sure, will turn upon the hunter.

Father – Drive us not to the madness of despair; we are told that you have laws which guard and protect the property of your White Children, but have made none to protect the rights of your Red Children. Perhaps you have expected that the Red Skin could protect himself from the rapacity of his pale faced bad brother. [12]

The lieutenant governor promised action but sent a second commission to the Sault to talk to the assembled chiefs. The chiefs were grievously disappointed to learn that the commissioners were not treaty commissioners. Councils were held again, statements provided, but most galling of all was the commissioners questioning the claims of the Anishinaabeg title to the land. All the while, mining activities continued unabated. The words that were printed in the Montreal Gazette in July 1849 turned out to be prophetic, and the chiefs decided to act. Shingwaukonse, then an old man, reportedly assembled a posse and dressed up as warriors with their faces painted, brandishing war clubs and “scalping knives.” The posse took a cannon and two six-pound howitzers and set sail from the Sault and took over the mine at Mica Bay on 11 November 1849. The government of the time, and some modern academics writing about this incident, identified lawyer/ speculator Allan MacDonnell as the ringleader, which minimizes the role and influence of Shingwaukonse and his young men.[13] The “Indian Troubles” as it was referred to, received a strong reaction. The Lieutenant Governor ordered that troops be sent up immediately but the full force never made it up to Mica Bay due to weather conditions. Nevertheless, the two chiefs and others surrendered on December 4, 1849 and were taken into custody. The chiefs were transferred to Toronto and thrown in jail where they remained until January 10, 1850.

A treaty commission was struck and William Benjamin Robinson was given instructions on the parameters of the terms that he could enter into on behalf of the Crown. Robinson travelled to Sault Ste Marie in September 1850 and had two treaties signed, the Robinson Huron and the Robinson Superior treaties. Shingwaukonse signed the treaty, but he did so begrudgingly as he did not get the terms that he had fought for and wanted. The commissioners, being practiced at the art of divide and conquer, split the chiefs’ opinions and secured the signature of others, resulting in Shingwaukonse having to fall in line.

It is important to note that Shingwaukonse knew that his band owned the land and everything upon and in it, the timber, the hay, the fish, the animals, and the minerals. It is also important to note that he wanted a monetary share from anything removed from his territory. After at least 13 years of councils, petitions, diplomatic missions, and an armed stand-off, Shingwaukonse was able to bring the government to the negotiating table and was able to secure a treaty with an annuity for perpetuity, an annuity that was supposed to increase once the province received profits enough to not incur a loss. Today, many people in the Robinson-Huron Treaty area receive their four dollars and many make remarks about how pitiful the amount is, but many may not realize that if it were not for the sustained efforts of Shingwaukonse, they would not be lining up at all, and perhaps no further treaties would have been signed after 1836. At that time the government seemed content to ignore Anishinaabe rights and turn a blind eye to their treaty obligations, while opening up the way for speculators, prospectors, businessmen, and companies. Doesn’t this scenario sound similar to the situation that Idle No More is responding to?

It is fitting then to close with two quotes from Shingwaukonse. The first quote speaks about the Anishinaabe oral tradition and its reliance upon memory, wampum, pipes and honour, and the importance of knowing one’s history and customs:

Father- We salute you, we beg of you to believe what we say for though we cannot put down our thoughts on paper as you, our Wampums and the records of our old men are as undying as your writings and they do not deceive.[14]

Ojibwe Chief Shingwaukonse relied upon the records of his old men. In fact, it was the records and training from his old men that compelled him to fight for what he believed in. This solid educational foundation as a leader gave Shingwaukonse the tools necessary to bring the representatives of the Crown to the negotiating table. It was not easy and it took years but Shingwaukonse’s dedication, commitment and compassion for his band would not be denied. This is the topic of his second quote:

Father – When I behold my red children which I shall leave behind and reflect on their present condition, and future prospects, and contrast their condition and prospects with the inhabitants opposite to us, and their country filled with plenty, I confess to you my heart ceases to beat with its accustomed energy, I feel ashamed and I indeed despair.[15]

Ojibwe Chief Shingwaukonse of the Jiichiishkwenh (Plover) clan, was a trailblazer in fighting for our rights. He considered not only himself but also the future generations of his people in every move that he made. This summer, when we take action, when we decide to no longer remain idle, it is the image of Chief Shingwaukonse who should inspire us.

[1] “Reply of Chin-gua-konse, a Chippewa Chief, August 183[8], S20 James Givins, Indian Papers – Transcriptions, Metro Toronto Reference Library, Baldwin Room.

[2] Chiefs of Mahnetooahning, 10th August 1846, In reference to the white people, [NAC RG 10, Vol. 122, p. 5942 – 5945].

[3] Chiefs of Mahnetooahning, 10th August 1846, In reference to the white people, [NAC RG 10, Vol. 122, p. 5942 – 5945].

[4] Chiefs of Mahnetooahning, 10th August 1846, In reference to the white people, [NAC RG 10, Vol. 122, p. 5942 – 5945].

[5] [Journal of Legislative Assembly, Appendix T, Appendix No. 48]Minutes of the Speeches made by the different tribes of Indians in reply to Lieutenant Colonel MacKay’s of the 11th of July 1829.

[6] The second speech of Chin-qua-kons [1837], S20 James Givins, Indian Papers – Transcriptions, Metro Toronto Reference Library, Baldwin Room.

[7] Speech of Shingwaukonce, 27th May 183[8], [Samuel Peters Jarvis Papers, Metro Toronto Reference Library, Box 61, p. 33].

[8] Speech of the Chief Shinguack [Shingwaukonse] delivered at Saut [sic] St Marie, August 20th, 1839, Samuel Peters Jarvis Papers, Metro Toronto Reference Library, B57, pp: 384 – 395].

[9] [NAC RG 10, Vol. 122, p. 5942 – 5945], Chiefs of Mahnetooahning, 10th August 1846, In reference to the white people

[10] Letters from the New Canada mission: 1843 – 1852, Part 1, (2001), Lorenzo Cadieux, s.j., translated by William Lonc and George Topp, s.j., p. 485-486.

[11] Letters from the New Canada mission: 1843 – 1852, Part 2, (2001), Lorenzo Cadieux, s.j., translated by William Lonc and George Topp, s.j., p. 16.

[12] Letters from the New Canada mission: 1843 – 1852, Part 2, (2001), Lorenzo Cadieux, s.j., translated by William Lonc and George Topp, s.j.[Source: Montreal Gazette, 1849, July 7]

[13] For Allan MacDonnell as the primary instigator see Nancy M. and W. Robert Wightman, “The Mica Bay Affair: Conflict on the Upper Lakes Mining Frontier, 1840 – 1850,” Ontario History, Vol. LXXXIII, No. 3, September 1991. For an interpretation that accords more agency and influence to Shingwaukonse, see Rhonda Telford, “Aboriginal Resistance in Mid-Nineteenth Century: The Anishinaabe, their allies, and the closing of the mining operation at Mica Bay and Michipicoten Island,” in Blockade and Resistance: Studies in actions of Peace and the Temagami blockades of 1988-89, 2003.

[14] Speeches of Chiefs in response to hearing the discontinuation of Indian Presents, Manitowaning 1852, [NAC RG 10, Vol. 198, pt. 1, No. 6101 – 6200, p. 116405 – 116408].

[15] [Samuel Peters Jarvis Papers, Metro Toronto Reference Library, B57, pp: 384 – 395] Speech of the Chief Shinguack [Shingwaukonse] delivered at Saut [sic] St Marie, August 20th, 1839

The picture of Quanah Parker, Apache Chief, is a bit of a misrepresentation..

Yes, I do not know why they included a picture of Quanah Parker, Comanche Chief.

Pingback: Trees as Historical Markers and Holders of Memory – Active History

Thank you for this, Alan. You are a good teacher. I hope to learn more!

Ron Stringer

Excellent article. There is often responses in main stream media about how we shouldn’t have to reconcile. Land was taken often in history they say….well wars often move land, but this, this is just theft. And as we so often put savagery on the native people, here we see diplomatic, peaceful ways and the result of those attempts.

Pingback: Mica Bay Incident - The Canadian Encyclopedia - Financial and Business News